Observations by David Robertson, 9/8/23

Back to work after the summer and stocks are starting to wilt. Let’s dive in.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

As Jim Bianco reports, Nasdaq performance year-to-date has been the best on record since total return data began in 1999. While improbable in many respects, it certainly captures the mood of the market.

Nasdaq performance has been even more exceptional given the rise in long-term rates year-to-date. The 10-year Treasury yield rose in the first quarter, cratered during the mini-banking crisis, and has been pretty much going up since the second quarter started. The graph below (with 10-year yield inverted) from themarketear.com ($) illustrates the scale of the gap.

On this note, AAPL is probably a good stock to keep an eye on. After an almost uninterrupted run up from the beginning of the year, the stock took a digger after July, rebounded weakly, and is now selling off again. As a market bellwether, where AAPL goes, so goes the S&P 500.

Finally, this tweet from Wall Street Silver seems to capture the mood well:

Labor

Here is Ben Hunt’s take on the labor environment, which I consider to be a highly qualified one:

Most interesting macro takeaway from meetings with CEOs this week…

“At least we can fill job openings now, but at every talent level we have hired for over past 2 years, we are SOOO overpaying for the work output we are actually getting.”

Every CEO in violent agreement w/this.

Fortunately, there is also good news on the labor front …

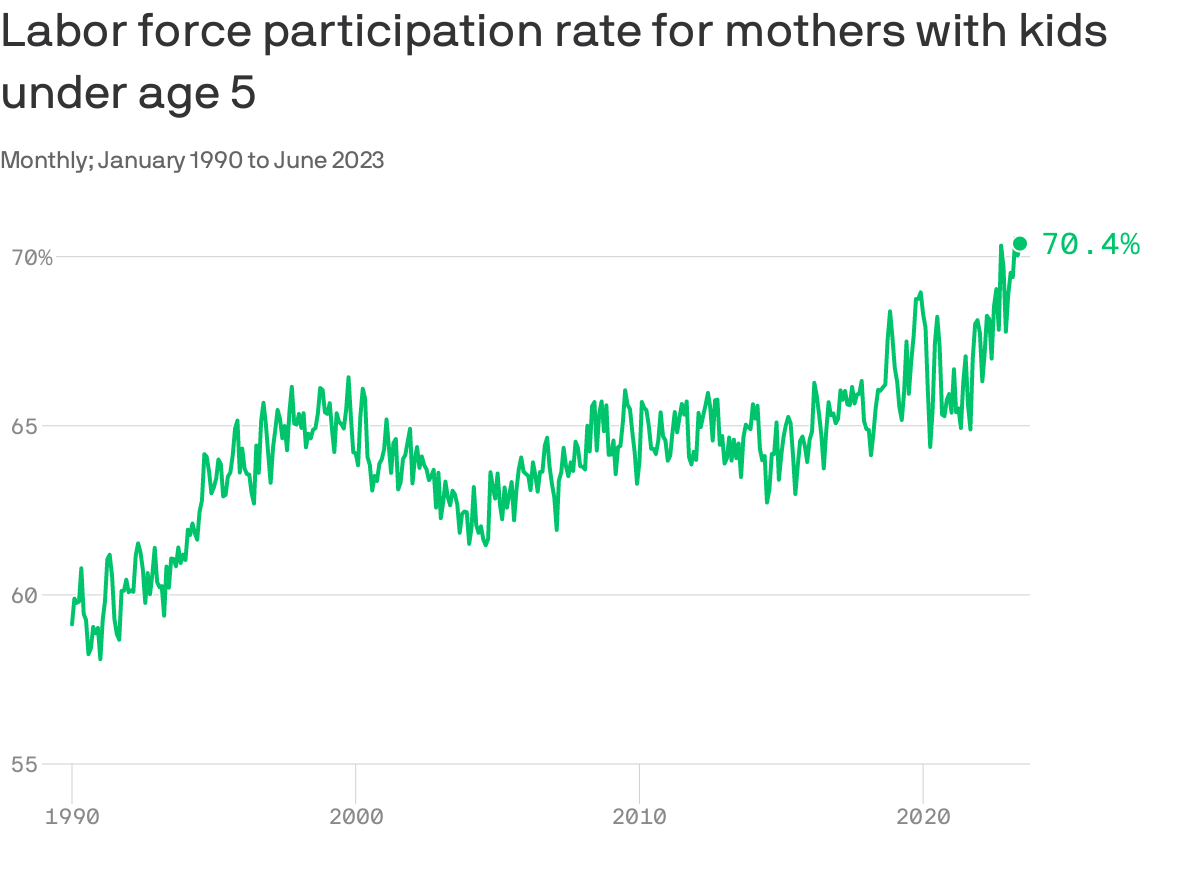

1 big thing: Women's "shocking" workforce return

https://www.axios.com/newsletters/axios-markets-e6c2ad13-7104-41cd-ab1c-1401678ea50d.html

Defying all expectations, the percentage of women in the workforce with young children is significantly higher than it's ever been, finds a new report from the Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution.

What happened: More research needs to be done, but it looks like a big factor is remote work, which enabled more women to stay attached to the workforce.

The women who were highly educated, and more likely to work from home, were among those more likely to be in the workforce now than pre-pandemic.

Plus, as other research has found, the pandemic — and ability to work remotely — may also have led more families to decide to have babies.

The first point is this is yet one more case of what appears to be a permanent change arising from the pandemic. At this point, it seems disingenuous to consider such changes as transient deviations that will eventually revert to the “norm”. No, the pandemic reordered certain parts of our lives for good.

In this particular case, it is a good thing in a couple of ways. First, to the extent mothers with kids represent a talented and valuable part of the work force, greater utilization of that talent is a bonus for the overall economy.

Second, it certainly appears as if the pandemic served as a useful impetus for establishing policies more compatible with people who have other important obligations - like parents of young kids. This suggests pre-existing policies were not as parent-friendly as they could have been and also suggests there is room to explore other policies to lure under-utilized workers back into the work force.

At a time when labor is tight and demographic growth is weak, it is especially encouraging to discover some modest tweaks to policies can go a long way to alleviating the problem. I vote for even more of this!

Inflation

A pithy and insightful tweet here from Lyn Alden on inflation:

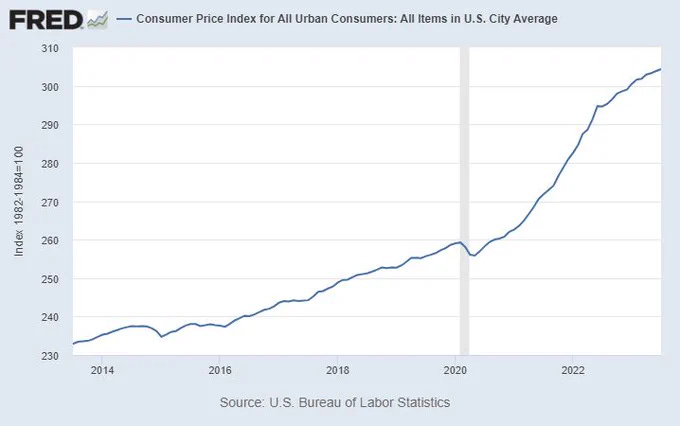

If supply chain disruptions were the main driver of price inflation rather than the growth of the money supply, then aggregate prices should go back down to their pre-COVID baseline, rather than remain at a permanently higher plateau and above-trend.

While there are better and worse takes on the “transitory inflation” thesis, it is strikingly clear from the graph that “transitory” has not entailed quick reversion back to original price levels. At best, it refers to a step-function higher level of prices. As such, there is little for consumers to cheer other than the fact that currently, things are not getting much worse on the price front.

This also highlights the uneven dynamic of inflationary pressures. Once price levels go up, there is an effort for workers to retain the purchasing power of their labor through pay increases. Some have more power to effect such increases and do so quickly. Others have less power and/or rigid contracts that only get renegotiated infrequently.

One consequence is wages do not rise uniformly or consistently in response to inflation. They tend to adjust in a ratcheting fashion, in a pattern of rising and then pausing. As a result, it takes time for wage pressures to cycle through - and impart their own pressure on rising prices.

The end result is an adjustment process that is ongoing, irregular, and difficult to reverse. This creates what might be thought of as latent inflation - wage increases that are likely to be coming down the road but haven’t hit yet. The most visible of these are punctuated by strikes, which are popping up all over the place. The bottom line is that a slow down in the inflation rate should be considered more as an indicator of an irregular adjustment process than of a reversal of price increases.

Inflation in the Twenty-First Century Part III: A Circular Flow No Longer ($)

https://kevincoldiron.substack.com/p/inflation-in-the-twenty-first-century-14f

China & the Oil/Commodity countries seem unlikely to buy more Treasuries.

Indirect purchases through financial centers will continue, but I bet these taper off as countries worry about the US improving its ability to trace the bonds’ ultimate ownership.

The Fed is trying to reduce its Treasury holdings.

In other words, some huge buyers want to stay on the sidelines.

At some point the Fed is going to get squeezed. It could get squeezed into allowing inflation to run higher because inflation is a stealth tax and what better way to finance a stubborn deficit than a stealth tax.

And it could get squeezed into keeping long-term rates low through buying bonds. Fed bond buying was not inflationary in the pre-Covid world, but purchases designed to finance a deficit would be.

I was very pleasantly surprised to come across the Substack of Kevin Coldiron, one of the co-authors of The Rise of Carry. That book was very influential for me because it explained the mechanisms and dynamics which facilitated the long period of low volatility and rising markets that dominated the period between the GFC and the pandemic - and which still emerges periodically as an important force.

In this post, Coldiron addresses a subject I have touched on several times - the supply and demand of US Treasuries. This is important because it explains something conventional economic theory has failed at for decades - which is explaining longer-term US Treasury yields. While economic pressures are a factor, the supply and demand are where the rubber hits the road. In this regard, the outlook is not good: Supply is growing while demand, especially from some historically big buyers, is fading.

The main point is one I think is underappreciated. Almost regardless of what the Fed does, there is likely to be inflation. “It could get squeezed into allowing inflation to run higher”, and, “it could get squeezed into keeping long-term rates low through buying bonds”. The bottom line is, “the flow of dollars around the world has changed and that makes the mechanics of financing the US deficit more challenging, which in turn increases the likelihood that inflation will be used as tool to manage it”.

Monetary policy

The NY Fed Trading Desk's Time to Shine? ($)

https://theovershoot.co/p/the-ny-fed-trading-desks-time-to

Thus, just last week, the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City hosted Darrell Duffie and Jeremy Stein to discuss the subject [illiquidity in the Treasury market] at the latest Jackson Hole Economic Symposium. (Theirs were the most interesting set of papers at this year’s symposium, at least as far as I am concerned.) Both agreed that contraints on dealers were a serious problem that prevented them from stepping up to buy bonds, and that some of those constraints were attributable to regulatory choices that might be worth revising.

If the point of maintaining “market functioning” is to prevent spikes in yields that could hurt borrowers in the real economy while facilitating transactions of bonds for cash, central banks are already better-positioned to do those trades directly than anyone else. What would be the point of involving intermediaries, except to pay them for a service that could provided in-house?

In what appears to be an instance of significant coincidence, a topic I raised in Observations from 8/18/23 also happened to be the subject of a paper discussed at Jackson Hole. The subject was Treasury market liquidity and the various alternatives available to ensure proper market functioning.

The point Matt Klein makes, which is a good one, is there are some things that are better to do yourself. In the case of the Treasury market, the prominent involvement of dealers seems to be problematic in almost every way imaginable other than by providing some slim semblance of a market place. If the problem to be solved for is to ensure there is always a buyer of Treasuries, having the Fed step in as the buyer of last resort makes sense. This “solution” invites other problems, but there are no silver bullets here.

In my discussion from 8/18, I characterized the effort by the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC) to shore up Treasury liquidity as “a concerted effort to shore up demonstrated weaknesses”. The discussion by Duffie and Stein (above) seem to corroborate that. Nonetheless, there are still those who seem to believe any actions by the Treasury or the Fed constitute efforts to artificially boost liquidity and/or suppress volatility …

The Coming Volatility Suppression ($)

https://concoda.substack.com/p/the-coming-volatility-suppression

By committing to purchase virtually unlimited amounts of U.S. Treasuries [in regard to Treasury market illiquidity in March 2020], the Fed’s “volatility suppressor” was born. U.S. sovereign debt was shown to only be truly risk-free when paired with added monetary alchemy and intervention from the Federal Reserve. Extensive central bank intervention was the only solution to stabilizing the value of “safe assets” backing trillions of dollars in funding transactions.

I found this piece especially interesting because it combines a really good background on funding markets, notable regulations, and important changes over time with an indomitable spirit of conspiracy. Despite the obvious efforts by TBAC to address the Treasury liquidity problem, and despite the clear focus on the problem by Duffie and Stein in a highly visible setting, Concoda isn’t buying any of it. Rather, the belief is, “Next time [i.e., the next event of Treasury illiquidity], it [the Fed’s response] will be no different. When another inevitable black swan surfaces, the Fed’s playbook remains unchanged.”

On one hand, I am sympathetic to the overarching belief that when push comes to shove, the Fed will capitulate and suppress volatility. After all, that has been it’s modus operandi for at least twenty-five years. Further, if worse does come to worse, the Fed should act to prevent a disaster.

On the other hand, however, the casual dismissal of the Fed as a volatility suppressing machine with an itchy trigger finger mischaracterizes risks that are relevant to investors. For one, it glosses over broader efforts to improve the resilience of the Treasury market and the creation of an expanded policy response toolkit. As a result, it fails to account for the new reality that the need for large scale bond buying is considerably lower than it was before. The banking crisis in March was a good example of the new, more targeted, policy response. The Fed’s playbook has changed.

Further, the tendency to focus on the Fed’s role as volatility suppressor overlooks the increasingly tenuous position the Fed is in. The Fed’s purchase of bonds is no longer the silver bullet it once was - and the Fed knows it. The Fed would only resort to large scale bond purchases again if it believed the consequences of not doing so would be worse than the massive inflation that would be set off by doing so. As a result, this inordinate belief in the Fed’s tendency to suppress volatility, while not entirely wrong, gives false hope.

Investment landscape

How Smart Is the Meme Stock Crowd? Go, See the Movie ($)

The most interesting is called simply Finfluencers, written for the Swiss Finance Institute by the academics Ali Kakhbod, Seyed Mohammad Kazempour, Dmitry Livdan and Norman Schuerhoff. It’s worth reading in full. The basic research involved analyzing tweets of investment advice from influencers that appeared on Stocktwits, and then gauging from subsequent results whether they had demonstrated genuine skill. Orthodox financial theory would predict that they would be normally distributed with few showing genuine repeated ability to beat the market. It would also suggest that investors would over time tend to crowd around those who appeared most gifted — a form of “return-chasing” that has long been demonstrated in flows into mutual funds.

But that’s not what the researchers found at all:

28% of finfluencers provide valuable investment advice that leads to monthly abnormal returns of 2.6% on average, while 16% of them are unskilled. The majority of finfluencers, 56%, are antiskilled, and following their investment advice yields monthly abnormal returns of -2.3%. Surprisingly, unskilled and antiskilled finfluencers have more followers, more activity, and more influence on retail trading than skilled finfluencers.

Once again, we were hoping for flying cars, and instead we got 140 characters - with which to dispense bad investment ideas apparently. The finding that unskilled and antiskilled contributors have more followers and more influence on retail trading than skilled ones isn’t terribly surprising, but it does highlight some important issues.

One of those issues is motivation. What are contributors and investors each trying to get out of the interaction? One of the points Rory Sutherland makes repeatedly in his book, Alchemy: The Surprising Power of Ideas That Don't Make Sense, is people often give rational, logical reasons for why they do things, but actually do them for very different reasons. I would argue the vast majority of investment “advice” on Twitter isn’t really about investment merits, but rather about things like status, attention, in-group camaraderie, and the like.

This is true of both retail and profession investors, and it is true of both contributors and investors. The main point is the business of investment advice is largely one of telling stories. While this suits many people just fine, it explains why it is so hard to get good investment insights for those who are earnestly seeking them. Of course, that endeavor is made harder yet by the pull of social proof, which often endorses the least qualified sources. Nobody said it would be easy!

Investment advisory landscape

This chart of retirement savings was highlighted by Michael Kitces. He asks a fair question: “Are our 'typical' clientele actually a lot further from the 'typical' American than we realize or care to admit?” In other words, does the investment advisory business mainly just serve as a concierge to the already wealthy? Is it even useful to society as a whole?

In general, I think the answer is mainly, no, the advisory business is not very useful to society. It focuses on a very narrow sliver of the population that are wealthy through hedge funds, private equity, venture capital and wealth management. For everyone else, it pushes products which have fees that are too high for what they do. This isn’t to say there aren’t a lot of good people in the business; there are. But it is hard to argue that as a whole, they are helping people achieve better investment outcomes.

A big part of the reason I founded Areté Asset Management was because I thought there were so many ways to do better - and I continue to believe that. Lower minimums, fair fees, transparent operations, and open communications are all part of that.

What has amazed me most is how little pushback there has been from investors themselves on the lopsided structure of the industry. Maybe a little market turmoil will motivate investors to search harder for good value propositions from their investment service providers.

Implications

Higher short rates haven’t taken out credit yet as spreads remain fairly tight, but they have taken a toll on small cap stocks, which are more credit-sensitive than larger cap stocks. As the credit noose continues to tighten, we are likely to see more and more cracks appear. The only question is whether they will continue to manifest as idiosyncratic instances or whether they will start to infect broader asset classes.

The longer end of the fixed income spectrum is also getting interesting as 10-year Treasury rates pushed over 4.29% this week. I continue to believe the supply/demand dynamics will cause long rates to continue to rise and if that is the case, long bonds will suffer.

Of course, stocks are also long duration securities and should also suffer from the increase in long rates. That has not been the case so far and presents one of the more interesting anomalies in the market right now. Is retail involvement in the artificial intelligence hype driving up stocks despite the fundamental headwinds? I suspect that is part of it. I also suspect continued inflows into retirement plans are still dominating any flows betting against large cap stocks though.

Regardless, it invites the question of when, and under what conditions, stocks will finally snap. One immediate possibility, as Zerohedge reports ($), is the possibility of a “vol [i.e., volatility] squeeze”. The report goes on to explain, “while this week may be a 'calm before the storm' moment; VIX seasonality, VIX levels, and VIX positioning all suggest plenty of ammunition for next week's event-risk cornucopia to create a 'vol squeeze’”. In other words, stocks could get shaken suddenly.

We’ll just have to wait and see. It may take time and other pressures to finally bring stocks down meaningfully. The main point is the evidence against stocks is accumulating. It’s dangerous enough to play Russian Roulette with a single bullet; it’s ridiculously dangerous to play with several bullets.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.