Observations by David Robertson, 12/23/22

Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays! I’ll be off December 30th and resume on January 6. In the meantime, best wishes for a Happy New Year!

As always, if you ever want to follow up on anything just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Year in review

This year has been an extremely eventful one and as a result I thought it would be appropriate to reflect on a few things.

For one, the year has proven more emphatically than I could ever argue that the investment landscape has fundamentally changed. There is no more, “set it and forget it”. The idea of bonds being safe and being useful diversifiers was shattered. Stocks took a hit but are still very expensive.

The obvious conclusion is that portfolio strategies will need to change in order to realize investment success. This is advice I embraced myself when I transitioned Areté’s flagship US equity strategy over to the new “All-Terrain” allocation strategy last year. As hard as it was to close down the midcap strategy, I couldn’t be happier about making the change. As the All-Terrain strategy comes up on its first full calendar year, its performance is proving the value of being flexible and thinking outside the strict bounds of just stocks and bonds.

A big part of that success has been a function of writing Observations. I started the letter shortly after the pandemic lockdowns began in 2020 as a way to keep clients informed on a more regular basis, as a way to share insights with other investors, and as a means to better chronicle and crystallize my own thinking. I couldn’t be more pleased with the way each of these goals has been fulfilled.

Looking forward, I fully expect the fundamental changes in the investment landscape to become even more fully manifested. This will require investors to make an ongoing effort to update and evolve their worldviews and mental models in order to succeed. In that vein, I will lay out some of the key models and working hypotheses that drive my view of the world in January.

Finally, above all else, thank you for all of your interest along the way. I really appreciate it!

Market observations

Stocks had a big down day on Monday, a big up day on Wednesday, a big down day on Thursday - all with very little news driving those moves. Probably the biggest news of the week came from the Bank of Japan (see more below).

I can quibble with a few points on this list but by and large it is a good summary of the important things to keep an eye on in the new year. A key theme will be the lagged effect of higher rates which means increasing difficulties for illiquid investments such as private equity and real estate. My list for 2023 features a relatively lesser focus on US politics and a relatively greater focus on geopolitics. More on that next year!

Re-opening

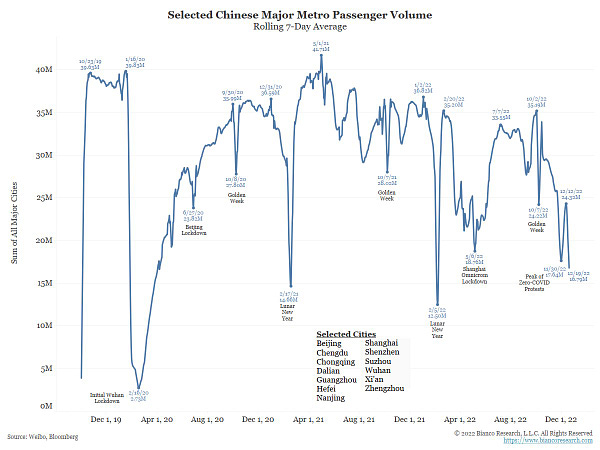

Jim Bianco (@biancoresearch) has done an excellent job reporting on Covid since the early days and picking up important trends in real time. Here he makes the case China isn’t going to be roaring back to life any time soon just because zero-Covid policies have been ditched.

Think back to just last year at this time in the US. Omicron was surging and causing all sorts of problems which I reported on at the time. There were direct problems of people being down with Omicron, but there were also indirect challenges such as severe shortages of healthcare workers. Many called it quits because it was just too hard to take care of people.

The main lesson is that Covid is extremely disruptive. There are no discrete boundaries on when it starts and when it stops. The effects permeate society for a long time …

To that point, Jim Bianco has also been right and early on recognizing that Covid has changed some things permanently, not least of which is the work standard of five days a week in the office. If a bustling metropolis like New York City is considering the reduction of subway service on Mondays and Fridays, the writing is on the wall everywhere else.

While disappointment will be experienced by a number of company leaders who want to hold court over their minions, as well as by a number of commercial real estate property owners, in general it appears the trend towards more flexible work arrangements is not only a very healthy adaptation, but a sustainable one as well. Silver linings!

Labor

Has the pendulum really swung from capital to labour? ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/30bfcfdd-c555-4c8b-94ba-97047c56ef5c

Labour shortages have persisted and wage growth has picked up quite strongly in some countries like the US and the UK. But pay hasn’t kept up with surging prices. As a result, global wages fell in real terms this year for the first time since comparable records began, according to the International Labour Organization.

Central bankers continue to fret about wage inflation getting out of hand. But this doesn’t look like a wage-price spiral to me. It looks like a living standards bloodbath.

So many important issues involved here and so little clarity of direction. One of the defining features of the last forty years was the success of capital relative to labor in the economic tug-of-war. As Sarah O’Connor explains, while “the mood does seem to have changed over the past few tumultuous years”, the “big question is whether any of that will survive an even tougher economic environment and a weaker labour market”. Good question.

It is an important question as well. Undoubtedly, there are lots of moving parts in the short-term, but longer term the political winds seem to be blowing in favor of labor. At some point, as Karen Ward from JP Morgan argues below, it many even be in the interest of central bankers to acquiesce to a higher base level of inflation …

What a new normal of higher inflation means for investors ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/6ec6f4c3-950b-439e-8361-0e22d92a17d6

Central banks might argue that if goods inflation is persistently higher, they will simply have to force service sector inflation lower. While correct in theory, the political reality is less clear. In a complete reversal of the experience of the past 30 years, service sector workers in the west would have to accept pay growth below the rate at which global goods prices were rising. Instead, I expect the central banks to accept a new modestly higher rate of inflation.

This is the type of situation that happens quite a bit in the investment world. It is not in the interest of central bankers or public policymakers to talk loudly about accepting a higher level of inflation. However, if that higher level of inflation does come to pass, it will have a big effect on portfolios and investment strategy. It will be important to keep ears to the ground to listen for subtle cues.

Geopolitics

On the one hand, analysts can look to exploding debt levels, out-of-control deficits, increasing inequality, and an increasingly fragile global monetary system and wonder why on earth the situation was allowed to get so bad.

On the other hand, given this is the situation we are in, one can hypothesize what would need to be done to solve all of these challenges. A strong dollar would certainly pinch global trade. Weakening global growth would also impair export markets. Higher inflation would eventually make debt levels more manageable. Higher interest rates would put labor on a more equal ground with capital and serve to reduce inequality.

I’m not going to claim the Biden administration cleverly engineered all of these solutions in order to solve a lot of intractable problems, but I think it is irresponsible to not seriously consider the possibility the Biden administration didn’t let the emergencies of Covid and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine go to waste. These events provided ample cover by which to accept the pain involved in creating a “new, better functioning trade and capital regime”.

I can hear skeptics screaming already but first let’s consider the explanatory power of the hypothesis. Let’s answer some questions. Given the large and growing trade imbalances, how would anything change other than unilaterally by the global hegemon? Large exporters like China and Germany would never agree to reduce exports voluntarily.

In addition, how could the US public accept relatively high inflation unless it was attributed to an almost universally despised figure like Putin? What better way to re-orient global trade than through a strong US dollar policy? By the way, what better way to weaken geopolitical rivals like Russia and China than by a strong US dollar policy?

Finally, one thing we have learned for certain is that neither Putin with the invasion of Ukraine nor Xi with the zero-Covid policy in China are strategic geniuses. It is that much of a leap to believe the combination of the US State Department, CIA, DoD, and other agencies can actually be fairly competent at times?

Regardless, the bad news is things are going to be tough for a while, but they will be a lot less tough in the US. The good news, if you can allow yourself to believe it, is the groundwork is being laid for a more prosperous and more sustainable future - and one that is still dominated by the US.

Japan

The BoJ flinches, but only a little ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/37d8e7a8-191f-4e6d-a251-cdc40ea68f49

What they’re trying to do is an orderly, slow exit from an unsustainable monetary policy regime. Now, they can’t say that, but that’s what they’re trying to do.

There’s no doubt in my mind that this is a step towards normalisation, but they’re trying to make it a really long process, as unexciting as possible, so that it doesn’t force selling by Japanese institutions . . . . They’ve seen what happens in the UK when you shock the government bond market . . . The genie is out of the bottle.

The Bank of Japan widened the trading band for the 10-year Japanese government bond which by various interpretations was anywhere from earth-shattering to almost trivial. Robert Armstrong and Ethan Wu do an excellent job putting the move into context and Mohamed El-Erian provides a thoughtful interpretation in the quote.

Japan is often considered the “Saudi Arabia” of capital because it has such large reserves of savings that roam globally looking for returns. As a result, when it becomes clearer to see a pathway for those assets to leave more distance venues and return home, the threat to risk assets rightly grabs a lot of attention. As with everything else, unsustainable policies must end one day.

Monetary policy

Great thread here from @dampedspring (Andy Constan) for those who are interested in better understanding liquidity dynamics. As I have mentioned many times before, liquidity is key to understanding market moves in the era of large central bank intervention and as I have also mentioned before (here and here), the net effect of changes in the Fed balance sheet, the Fed’s reverse repo program (RRP), and the Treasury’s General Account (TGA) has served to provide a very useful heuristic for understanding market action.

The main point Constan makes is, “it’s not that simple”. In short, the importance of changes in TGA are a function of the nature of its funding. If it is funded by longer-term bonds, changes in TGA do affect liquidity. If it is funded by short-term T-bills, not so much.

All of this comes up in the context of recent, large, changes in TGA, which can mainly be attributed to the rapidly approaching debt ceiling threshold. In order to interpret those changes properly, you need to dig into the funding as well. Lots of moving parts.

Trapped Liquidity

https://fedguy.com/trapped-liquidity/#more-5609

An ideal QT would drain liquidity in the overall financial system while keeping liquidity in the banking sector above a minimum threshold. That is only possible if the bulk of the liquidity drained is sourced from the $2t RRP, which holds funds owned by money market funds. MMFs could facilitate QT by withdrawing funds from the RRP to invest in the growing supply of Treasury bills, but recent data suggests they have lost interest in bills.

Another piece on the subject of arcane, but important, monetary policy details. The general issue addressed is that the Fed’s QT program will start running into the significant constraint of minimum threshold of bank reserves before too long if something doesn’t change. Fedguy Joseph Wang concludes this will limit the duration of the QT program, which would halt the persistent drain of liquidity.

While I have a great deal of respect for Wang’s knowledge of monetary policy details and Federal Reserve operating procedures, I am at least somewhat skeptical about jumping to the same conclusion about policy direction. For starters, the Fed discarded any kind of rulebook for normalcy when it completely upended the paradigm for monetary policy during the GFC back in 2008.

In addition, it seems as if the overall goal of policy has reversed. Originally, monetary policy during the GFC was established with the goal of dampening volatility and quelling the emergency. Now, the goal is to dampen inflation - and the only way it can do that is by slowly, gradually, carefully reducing the mass of liquidity it created during both the GFC and Covid emergencies.

In short, the goal of the Fed now is to undo what did in spades before. It must do so quietly, however, so as to not implicate itself in the crime of inflation. As a result, I expect the drawdown in liquidity to also happen quietly. This means no grand strategy will be publicized nor will policy changes be announced ahead of time. Rather, when the liquidity reduction program does run into friction, regulations and policies will be adjusted to facilitate its continuation. This process may not always be smooth, but I think its direction is pretty clear.

Investment landscape

Asset Allocation In Financial Repression: Governments Decide Whose Naughty And Nice ($)

Russell Napier hosted a call this week to talk about asset allocation in an era of financial repression. Napier has been early and right on inflation so I keep coming back to his framework.

One big point that I believe is significantly underappreciated is the mechanism of financial repression. It is not fiscal vs. monetary policy. Rather, it is the “capture of the private sector financial system for public sector gain”. In other words, “it is the takeover of banks to allocate savings”.

One objection to the concept of financial repression is that it makes absolutely no sense to asset managers and investors. True enough. Nowhere in economics or finance textbooks will you find the policy recommendation of government taking over the banking system to allocate private sector savings for the purpose of generating moderate inflation. It sounds patently stupid.

But that is exactly the problem. Politicians have a very different way of looking at the world. From their perspective, there is no better policy choice than financial repression. They are just working from different textbooks - those of history and politics.

Another objection to the potential for financial repression, and one I have considered myself, is the degree of political polarization. What is the effect of political gridlock on the potential to implement financial repression? “None”, answers Napier immediately. It is the one thing “everybody can agree on”.

So, to a greater or lesser degree, it looks like governments are on a path to commandeering their banking systems. One implication is, “monetary policy is run by government, not central banks”. This is clearly not a consensus view given all the song and dance that still accompanies Fed pronouncements and press conferences.

As such, it will be useful to mainly tune out the Fed’s three-ring circus. It is mainly a puppet in a grander affair at this point. It will be much more useful to assume bank lending will increase - which will increase money supply. The most useful activity will be figuring out which businesses and sectors will be favored by government policy.

Implications

In regard to the developing regime of financial repression, Napier explains the big change to understand is that “government changes the nature of commercial risk”. Favored businesses and sectors will receive cheap capital, guaranteed business and protected margins. Others will face a bleak credit winter on their own.

One of the main areas Napier suggests avoiding is overvalued stocks. That mostly also means overowned stocks - which in turn mostly means indexes. As he puts it, “overvalued equities kill you in inflation”. This will impact holders of large market index funds and target date funds among others.

Another area to avoid is financial engineering. Investment banking, private equity, commercial real estate, and share repurchases have all provided channels by which to exploit exceptionally low interest rates. In a world where inflation is higher, interest rates are higher, and public policy favors productive investment, however, these endeavors will be unceremoniously relegated to the sidelines.

The list of favored investments is shorter. Top on the list is gold. After all, the whole purpose of financial repression is to slowly and steadily debase the currency. Gold is the antidote to that process.

Also on the list are stocks that aren’t overvalued. Stocks that fly under the radar of major indexes and are reasonably valued, can continue to chug along with decent returns. A very interesting question mark is whether industrial and commodities companies will be able to weather progressive ESG pushback and rebrand themselves as “essential” companies. I happen to think the chances are pretty decent.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.