Observations by David Robertson, 1/20/23

It was a week filled with market moving news and market moves, but not always in the direction expected. The early days of 2023 are foreboding an environment which is anything but business as usual. If you want to follow up on anything along the way, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

After a bit of a rocky start to the year, the S&P 500 jumped over 4% through early Wednesday. Disproportionate gains were realized in highly speculative growth and meme stocks. Robert Armstrong and Ethan Wu at the FT ($) point out, “You would think that between high recession risk, the threat of margin compression, improving alternatives in fixed income and much else, equities would be paying a whole lot more than bonds. But no, it’s [the equity risk premium] at a decade low”.

Nor were the festivities been relegated to stocks only. As Almost Daily Grants (Tuesday, January 17, 2023) highlights, “It's a crypto comeback … the NYSE FactSet Global Blockchain Technologies Index, which tracks shares of various industry players, has exploded higher by 49% in the young year-to-date”.

Such speculation is also manifesting in new business creation …

You can’t make this stuff up. As @SilvermanJacob elaborates, “The founders of bankrupt crypto hedge fund 3AC are joining with the founders of bankrupt exchange CoinFLEX to start a new exchange. The 3AC founders have been holed up in non-extradition countries since their biz collapsed.” It really makes you wonder if operating within the law is a competitive disadvantage.

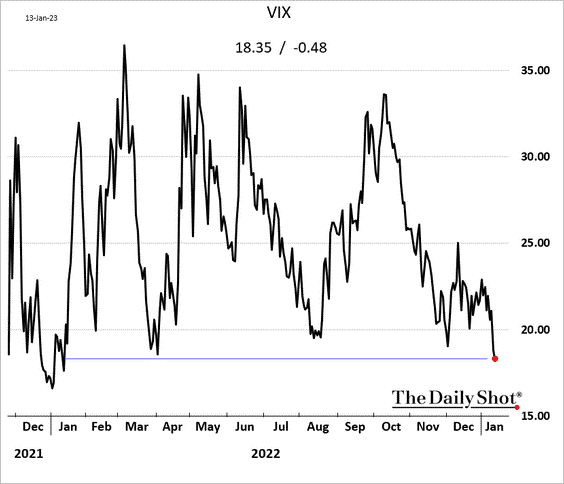

Finally, one of the usual suspects of speculative appetite, low volatility, is standing out as an accomplice. The chart below from @SoberLook shows VIX hitting its lowest level in a year.

Then stocks cratered on Wednesday and were down again on Thursday. Was it due to Russia? The debt ceiling? Something else? Who knows … c’est la vie.

Economy

Most of the data this week showed a weakening economy. Perhaps the most dramatic was news from KB Home in the tweet below.

One point is that it takes time for changes in interest rates to ripple through the business landscape and to cause changes in economic decisions. It looks like higher rates are now really starting to hit the housing market. It will take more time to gauge the broader effect on housing as well as the effect on commercial and other real estate. But it’s coming.

Another point is while the preponderance of data this week was bad, the labor data has been good and lower inflation data is good (for consumers) too. This hellish mix of wildly disparate data provides a fitting omen for the year.

China

The dominant narrative on China is the reopening trade. According to the storyline, once Covid has swept through the country, people will get back to work and the economy will jump to a higher level of activity from the lockdown-induced malaise of 2022.

A number of data points suggest higher growth in China is a fair expectation. Airline travel is quickly recovering, many business restrictions have been lifted or eased, and liquidity conditions have improved. While these are all positive signs, they encompass only part of the economic reality in China.

The other part of the economic story for China is one ridden with thorny challenges. Sure, some liquidity has been provided, but that is mainly to prevent the overgrown property sector from imploding in a deflationary debt spiral. Even problems in the property sector are only a symptom of the even bigger challenge of transitioning away from a supply-driven economic model.

If those challenges weren’t enough, China reported this week it’s population actually fell last year. As Peter Zeihan elaborates, this report is probably too optimistic. He figures China’s population started declining 12-14 years ago. Regardless, while there are indications of short-term incremental improvement, there also remain severe, long-term, structural impediments.

This raises another interesting point highlighted in the graph and image below from @SoberLook. China, driven by its large economy and supply-driven growth model, has been an extremely important factor in commodity prices. Recent actions to steer iron ore prices lower suggest not only is demand elastic, but it can be very deliberately so. Insofar as this is the case, commodity traders and investors will need to contrive entirely new demand models.

Japan

In essence, in late 1980s Japan was beginning to look like a strategic competitor to the US, and choose stagnation, and a peaceful life, rather than rupture with the US. I think this makes sense to me. Turning Japan from a strategic competitor back into a natural ally of the US is good statecraft, and given the disaster that World War II was for Japan, an understandable decision. Using this line of thought, Abenomics did indeed mark a political change in Japan, away from managed decline to something else.

Japanese monetary policy has been like the accident on the highway you just can’t stop looking at. Last year traders and investors were wondering just how low the Japanese yen could go. It certainly seemed as if the showdown at the OK Corral was imminent: Was it finally time for the Bank of Japan (BOJ) to give up on yield curve control or would it continue printing loads of money to artificially restrain rates?

Before there was any definitive resolution, the yen mysteriously started getting stronger. At the same time, the US dollar started weakening. Weird. Then, in what came across as a non sequitur, the FT reported ($) in December:

Japan will overturn six decades of postwar security policy and arm itself with one of the world’s largest defence budgets to counter “an unprecedented and the greatest strategic challenge” posed by China’s rising military aggression.

Hmmm. By the logic of economic and monetary policy, none of these things make sense. There is just no good explanation for them. This is exactly why I find Russell Clark’s perspective which is grounded in geopolitics to be so refreshing. His view provides a sensible explanation of the fact pattern.

Namely, the BOJ is stuck in a war it can’t win, but it would like to have some say in the terms of surrender. Whether it doubles down on yield curve control or eventually caves in, it would be far better to do so under the new bank head this year. Then the move can be billed as a policy change under a new leader rather than the inevitable outcome of failed policy of the past.

My theory is the US facilitated this transition by allowing the US dollar to weaken. In return, the US got a much stronger commitment to defense from Japan. This didn’t just happen. At a time when the US is aggressively establishing boundaries on interactions with China, having Japan as an ally in the region is crucial.

So, one point is monetary policy in Japan matters, but is virtually impossible to game out. As James Aitken explains in a Grant Williams podcast: “By the time the Bank of Japan feels compelled to do away with yield curve control, and by the way, there can be no forewarning, it’ll just happen … You can’t guide the end of a peg. It’s just not possible.”

Another point, however, is monetary policy is not the only game in town; geopolitics matters as well. On this count, Japan’s allegiance to the US will also matter a great deal.

Oil

What the end of the US shale revolution would mean for the world ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/60747b3b-e6ea-47c0-938d-af515816d0f1

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has precipitated a global energy crisis — and the US has been among the biggest beneficiaries. As Moscow has cut natural gas shipments to Europe and western sanctions have targeted its oil, American exports of both have soared. About 500 tankers laden with American oil have sailed to Europe since February 2022, according to data firm OilX, helping US crude exports hit a record high last year.

A lot of hubbub arose from the Biden Administration’s move last year to release oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR). Most of the takes were critical. Some of the criticism focused on the apparent reduction of strategic resources and other criticism focused on the apparent political motivation to lower gas prices in front of mid-term elections.

What can be seen more clearly with the benefit of hindsight and some perspective is the degree to which US actions in regard to oil were strategic. As Derek Brower and Myles McCormick point out in the FT article, “The flotilla of American oil and gas exports today has helped to neutralise Vladimir Putin’s energy war.”

The extra oil sent to Europe from the US kept Europe running in spite of its prior dependence on Russian energy and in so doing also strengthened the geopolitical relationship. The account is strikingly similar to one involving Britain in World War II as conveyed by Daniel Yergin in his book on the oil industry, The Prize.

Among those things to be “lent,” for repayment at some indefinite time in the future, was American oil. The neutrality legislation, which restricted the ability to ship supplies to Britain, was progressively loosened. And, in the spring of 1941, when oil supplies began to plummet in the United Kingdom, fifty American oil tankers were switched from supplying the American East Coast ports to carrying oil for transshipment to England.

One lesson is when push comes to shove, as in times of war, rules can change. They can also do so quickly and dramatically - because priorities can change quickly and dramatically. Analysts who don’t recognize the change are vulnerable to completely misinterpreting various actions.

Monetary policy

Liquidity Trader, Primary Dealer Report ($)

In December, as the Federal debt closed in on the statutory debt limit, the US Treasury started paying down T-bills with giant wads of cash. That took some of the selling pressure off the markets. It took T-bills out of market supply. At the same time, it stuffed cash into the accounts of money market funds, banks, and most importantly, Primary Dealers.

The dealers used that cash to pay down net repo borrowings to a 6 year record low. They were flush with cash. But they deleveraged their overnight spec money only. They continued to buy longer term Treasuries. Apparently, they also bought stocks.

For the time being, they’ll [the US Treasury] keep issuing bonds, while continuing to pay down bills. That has already dramatically slowed the upward pressure on T-bill rates in the market. Consequently the Fed is pretending that it is slowing its rate increases. It’s Kabuki theater.

In this weekly update, Lee Adler provides a lot of useful context around rates and monetary policy. For starters, he explains the unusual decline in the Treasury General Account (TGA) that started late last year as at least partly prompted by the effort to avoid violating the debt ceiling.

The logistics of managing the constraints of the debt ceiling mean the Treasury needs to re-orient its funding. Practically, this has involved maintaining the schedule of bond issuance while offsetting those sums by paying down Treasury bills. The lower supply of bills has “slowed the upward pressure on T-bill rates”.

This is interesting because many market participants have been reading the easing of short-term rates as evidence of an imminent Fed pivot. Obviously this interpretation is at best incomplete, and at worst, completely off base.

One thing to watch out for is the interaction of Fed and Treasury policies. With the Fed reducing liquidity and Treasury providing liquidity, the two are working at cross purposes, at least for the time being. Is there a reason why they aren’t working in a coordinated way?

Another thing to watch out for is what happens after the debt ceiling is resolved. Paradoxically, that limitation is leading to better liquidity conditions right now. Once debt issuance gets fired up again later in the year, however, those conditions will reverse in spades. The makings of a trap if ever there was one.

Finally, while it looks like the overall liquidity environment will be better than expected while the debt ceiling theatrics play out, that doesn’t change the Fed’s broader goal of draining excess liquidity through Quantitative Tightening (QT). As a result, much like with the economy, there promises to be a lot of mixed signals to disentangle this year.

Investment landscape

Market Sit-Rep January 18th, 2023

This appears to be the primary dynamic of 0dte options when net sold. As we've discussed repeatedly, this does not appear to be a retail story, but rather a regulatory arbitrage story. As an institutional investor, there's an intraday loophole. If I don't hold the position when my prime broker looks at my end of day books, I don't need to post collateral. And if I take a position that has a high probability of NOT being exercised... for example a 3% OTM daily option... then it's basically "free" money. Yes, a very risky deal with Faustus... but "FREE MONEY!!!!"

As they so often do, the folks at Tier1 Alpha provide some interesting insights into the market landscape. Why have zero-day-to-expiry (0dte) options become so popular? It’s mainly due to institutions engaging in regulatory arbitrage. In other words, “it’s basically ‘free’ money”.

One point is this is yet another manifestation of the carry regime I have mentioned many times in the past (here, here, here, here, and here). The most prominent characteristic is it creates a positive feedback loop whereby declining volatility begets buying which begets lower volatility - and so on. This helps explain the unusually low level of volatility and the weirdly persistent outperformance of stocks so far this year.

Another point is the feedback loop continues until something breaks it definitively, or as Tier1 Alpha describes, “until something conspires to deliver the exogenous, Volmaggedon-style, event”. This is especially notable in light of the Fed’s effort to engage in a controlled demolition of markets. The carry regime works against both of the Fed’s goals of “control” and “demolition” (at least in the short-term).

Will the Fed modify its policy or enhance regulation to mitigate the risk this phenomenon presents? Will it just plug ahead as if nothing is happening? Will it wait for a Volmaggedon-style event to enact emergency measures that would be intolerable otherwise? It’s hard to say and I certainly don’t have a crystal ball, but this is on my radar now.

Implications

The common thread running through each perspective of the investment landscape is uncertainty. There is bad economic data, but also good data. Liquidity conditions are still negative mid-term, but have been better short-term. Company earnings have been good, but look to be floundering now. We’ll be finding out soon enough.

In addition, there are a whole host of things that could cause serious ructions in the market. The economic outlook ranges from severe recession to soft landing. There has already been redemption pressure on illiquid funds; further problems could cause a scramble for liquidity. All this and we get a full season of debt season shenanigans too.

Japan could exit yield curve control and cause billions of dollars to leave foreign fixed income investments and return home. China is always opaque and unpredictable. Oh, and there is a war with Russia which could manifest in any number of unpleasant ways.

With this noisy backdrop, @hkuppy’s advice below is appropriate: When something is obvious, do it. But for most things, there is a good chance any decision you make will be the wrong one. Be patient and good luck.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.