Observations by David Robertson, 9/15/23

It was a busy news week and there is plenty to discuss so let’s jump right in.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

CPI dominated the news this week and the report on Wednesday was mixed. The headline number was up 0.6% for August and 3.7% for the last twelve months. The core number, less food and energy, was up 0.3% for August and 4.3% for the last twelve months.

While the report was not terrible, it also was not an “all-clear” signal that inflation has been defeated. Combined with the PPI report on Thursday, there was enough to support the views of both moderating inflation and increasing inflation. The increase in gas prices was a big factor. The main debate revolves around the degree to which such components are rising steadily or only temporarily.

In other data, new unemployment claims remained on the low side and retail sales jumped higher than expected. Based on this data, the economy is continuing to chug along at a pretty decent pace.

With the big dump of data this week, it is an opportune time to re-establish some context. There are still distortions working through the economy from Covid and related policies and there will be developing, yet indeterminate, effects from tighter monetary policy. As a result, individual economic data points just can’t tell us very much in real time. A certain amount of humility is useful here.

In addition, as I have noted before, government policy is playing a greater role than it has in the past. This means forecasts based on historical data alone are incrementally less useful for determining the economic trajectory. Similarly, it is incrementally more useful to incorporate policy objectives for these purposes.

In regard to the market, the graph above from themarketear.com ($) shows stock performance this year has not been a function of fundamental performance so much as whether the stock is related to artificial intelligence (AI) or not. If you take out the AI boom stocks, the rest of the S&P 500 is barely edging out cash this year. Not exactly a good case for diversification or performance.

Finally, we are rapidly approaching a possible government shutdown and almost nobody seems the least bit concerned about it. As Axios reports, “The House of Representatives needs to pass 12 appropriations bills needed to fund the government by Sept. 30 — and it hasn't yet passed a single one”. Tick tock.

Interestingly, the related item that is capturing headlines is the inquiry by House Speaker Kevin McCarthy to impeach President Biden. This appears primarily to be a concession by McCarthy to maintain some semblance of control over his unwieldy coalition, but certainly highlights the still-high level of political acrimony. As such, it provides a hint that this appropriations process may be more disruptive than past ones.

Commercial real estate

WeWork, too big to fail ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/9c284c8a-f893-463a-97cb-ce1af1a7f49b

The WeWork story makes it clear, once again, that floating-rate loans are not fully insulated from interest rate risk. In a higher rate environment, some tenants cannot meet their lease obligations, and so some asset owners will not be able to meet their loan obligations. Renegotiations or defaults follow. Lenders’ interest rate spreads over their cost of funding will tend to compress when rates rise fast.

The two stories raise an interesting question: from the point of view of banks exposed to CRE in cities where WeWork remains a significant presence, is the company too big to fail? In other words, is it better for the landlords to renegotiate with WeWork so that it can stagger on, rather than refuse and increase the odds of bankruptcy, putting its $13bn in existing lease obligations at risk? The company accounts for about 1.5 per cent of Manhattan office space. The market for office assets is near frozen, and financing is already scarce. Perhaps a high-profile WeWork bankruptcy shocks the market, sending valuation down another leg, triggering more defaults. I don’t know. But if I was one of WeWork’s landlords, or those landlords’ banks, I would be thinking about it. Hard.

The Unhedged column at the FT characterizes the challenges facing the commercial real estate sector by way of the example of WeWork. Ostensibly, bank lenders are protected from interest rate risk because the loans to WeWork are floating-rate. When short-term rates go up, so do the rates on the loans. No problemo.

However … when a single borrower accounts for a meaningful share of the market, as WeWork does with office space in New York City, the borrower’s problems become the lender’s problems as well.

This means lenders are not as well protected as they thought. It also means there is a good chance a number of the loans will get renegotiated. To the extent this happens, it will forestall the need for WeWork and other borrowers to close properties and/or restructure. This in turn will delay the need for the properties’ owners to reflect any impairment in value.

In short, the convenient fiction of a passable real estate market might be maintained for a little while longer. But not forever.

Politics

America’s New Right is moving beyond Reaganism ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/ec084628-12ca-429a-b5c3-37a5f29a4eda

You might say they [middle-American Republicans and Democrats alike] are more interested in community, family and work than wealth. And while “work not wealth” is a Biden policy slug, it also hearkens back to a less extreme kind of capitalism common a few decades ago. At that point many US communities were more economically diverse, focusing on both production and consumption, with less concentration of power within specific industries. There was also far less of the wealth inequality that has risen hand in hand with unchecked markets and greater private sector power.

This is important, because it means that trustbusting could now become a more bipartisan issue. The idea that private sector “tyranny” — in the form of outsized corporate economic and political control — is threatening individual liberty in America is an issue that is being taken up as a rallying point by conservatives and progressives alike.

The first thing that resonates with me about this piece is the description of middle-American Republicans and Democrats as being more similar than different. As someone who grew up in Iowa, I can attest to interests in “community, family and work” being of more interest than wealth. This creates a very different ethos than on the coasts where wealth and political rivalry seem to occupy much greater mind share.

Another thing that strikes me about this piece is the highlighting of political issues that are getting support from both sides. Rana Foroohar explains how “trustbusting could now become a more bipartisan issue”. By virtue of showing up in the FT, it suggests the areas of bipartisan agreement are becoming something of a “thing”.

It also corroborates my idea that such areas of bipartisan agreement could constitute the foundation of a broader social transformation a la a second regeneracy in the Fourth Turning (mentioned here and here). Indeed, it is not hard to see how some of the ideals of the past such as individual choice, especially at the expense of moral hazard and economic and generational inequality, map well to some of Howe’s social transformations. Examples include moving from individualism to community, moving from privilege to equality, and moving from deferral to permanence.

One possible scenario would be the establishment of a third party that would embrace the multiple areas of bipartisan agreement and steal the center of the political spectrum from the two major parties. If successful, it could force the reformation of both major parties.

Another possible scenario would be the integration of many policy planks that enjoy bipartisan support into one of the existing major parties. Personally, I think this would be more likely for Democrats than Republicans, but either is possible. In this case, the successful party could emerge dominant, with the political capital to drive major public policy changes.

Perhaps what I find most interesting about these hypotheses is how improbable they were just three years ago. But this is how crises emerge and how Fourth Turnings evolve: Nobody expects it.

Liquidity

The liquidity playbook for the last year and a half or so has focused on big government drivers such as the Fed’s Quantitative Tightening (QT) program, Treasury’s general account (TGA) and the Fed’s reverse repo (RRP) program. Aggregate changes in these have corresponded closely with overall liquidity conditions.

One assumption behind all that, however, was that bank lending would remain subdued. Not only were rising rates increasing the cost of borrowing, slow economic growth mitigated the desire to borrow. That may be changing though.

Total loans and leases in bank credit, as reported in the Fed’s H.8 credit report, show steady increases through each week in August. Sure, banks will need to deal with rising credit costs, and capital issues may constrain growth to some extent. If credit provision continues to increase, however, it would be a very strong signal for overall liquidity. Best keep an eye on this one.

Investment landscape

World to Tokyo — Message Received ($)

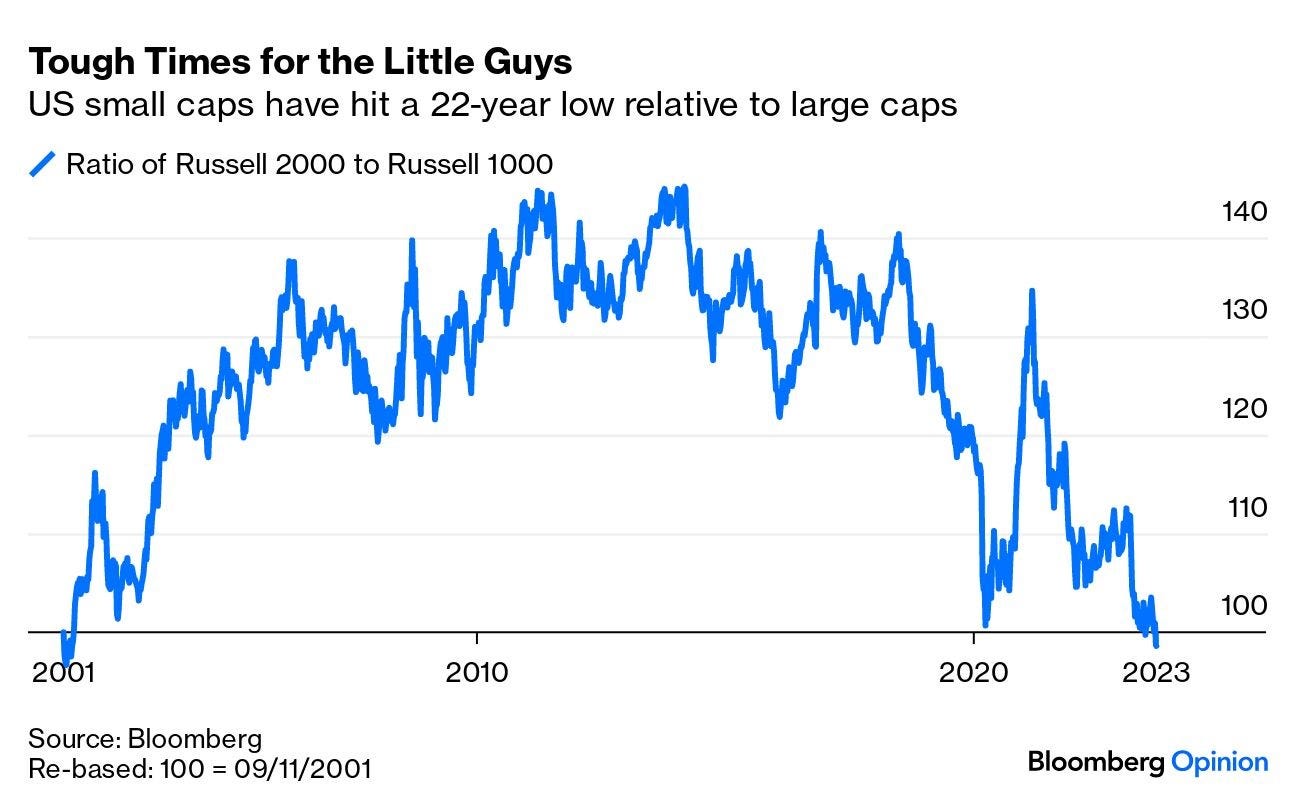

Small companies generally outperform big ones. That’s because they have greater room to grow, and because they’re riskier, meaning that the premium for buying them will be larger. The size effect has long been recognized in the academic literature. But in the US, at least, small-company performance has taken a long hiatus.

But a deeper driving factor could be the bizarre state of financing in the US. Smaller companies tend to use floating-rate debt (they often don’t have a choice about this), and so higher rates are already hurting them. Bigger companies used the exceptionally long period during 2020 and 2021, when rates were effectively zero, to lock in low rates well into the future.

John Authers rightly highlights the phenomenon of small cap underperformance relative to large caps. While the relative performance has been fairly even over the last twenty-two years, small caps have gotten seriously outpaced since the early 2010s.

By all rights, small caps should outperform - both due to higher growth prospects and higher risk. Historically they have outperformed. The question is, why have they underperformed so significantly in recent years?

There are a lot of possible answers to this. Borrowing costs surely explain some of the recent woes. Not only are small caps often subjected to variable rates, which have risen a lot, but their large cap brethren often borrow through capital markets and many have been able to lock in low rates for many years.

In addition, as central bank authorities have fallen all over themselves trying to prevent financial instability since the GFC, markets have interpreted the moves as a backstop for financial markets. In other words, traders and investors are assuming the Fed will always step in to save markets if things get bad enough.

This dynamic has amplified a “carry” regime whereby selling volatility is a very profitable trade - because (as the belief goes) whenever volatility shoots up too high, the Fed will do something to bring it back down.

For these reasons and more, small cap stocks have just not had a level playing field with large caps for most of the last twenty years. Interestingly, monetary policy has its fingerprints all over the crime scene. Normalize volatility and credit and there’s a good chance small cap performance relative to large caps would look a lot better.

Also very interesting are the political consequences of monetary interference. By raising interest rates, the Fed is trying to slow inflation down, but by doing so it is also disproportionately harming smaller businesses. At a time when “rebuilding” industrial production in the country comprises important economic and geopolitical goals, creating disadvantages for small companies is a major problem.

What could cause things to change? If current trends persist, monetary policymakers will be confronted with a terrible choice: Either persist in fighting inflation with higher rates (and continue crippling smaller businesses), or ease up on the monetary pressure (and allow inflation to jump higher). I’ll bet on the latter, but not yet.

Investment strategy

Two's a Crowd? ($)

https://www.yesigiveafig.com/p/twos-a-crowd

In a hypothetical scenario of a 100% passive market with fixed allocations, bond and equity prices would be determined solely by the intersection of savings flow and supply of bonds and equities. This could allow equity valuations to rise even as bond prices fall (yields rise), mainly because demand is fixed and supply determines the price.

Well, remember that institutions, like insurance companies, that must match assets and liabilities experience a net BENEFIT from rising interest rates. The discount factor used for their liabilities rises, typically leading to a net funding benefit. Perversely, this LOWERS demand for bonds even as they become empirically more attractive.

My hunch is that it’s tied to increasingly inelastic portfolio allocation techniques — target date funds, model portfolios, etc. In other words, US government bonds are the asset being crowded out. This means that bonds can become incredibly cheap relative to US equities, but the reversal is likely to be quite violent if we see investors eventually challenge these allocation models.

Anyone paying close attention to the market and being completely honest has been at least somewhat confounded by the rise and rise and rise of stocks since the GFC. Most commentators do little more than attribute such performance with clichés such as “Earnings growth!” and “Fed easing!” that are both meaningless and thoughtless. As a result, I have a lot of respect for Mike Green in that he is one of the few people who has actually been trying to figure out what is going on rather than just shrugging and spewing out trite soundbites.

As I have reported in the past (here, here, and here), the “Inelastic market hypothesis” explains how the rising share of passive investing facilitates ever-rising valuations for stocks. One updated observation Green makes in his recent piece is, “We are experiencing an anomaly where despite rising real risk-free bond yields, there has been no structural re-rating of U.S. equities.” While this is odd, it does provide confirming evidence of inelastic markets.

Green also pursues the implications of inelastic markets for bonds. Since higher rates mean lower liabilities for very large buyers of bonds like insurance companies, the demand for bonds can go down even as bonds become progressively cheaper (i.e., higher yielding). Further, this can happen as stocks remain expensive because the demand for stocks, through target-date funds and the like, remains undiminished. As a result, “bonds can become incredibly cheap relative to US equities”.

This has really big implications for investors. First, the fact that bonds are becoming more attractive relative to stocks doesn’t mean the trend can’t continue for a long time. Second, when stocks do finally get sold off, “the reversal is likely to be quite violent”. These present monstrous challenges for asset allocators and vastly complicates the traditional focus on stocks and bonds.

Implications

One of the comments that is often tossed about as a rebuke to holding a lot of cash is that it effectively amounts to timing the market. Since such timing is virtually impossible to do, it doesn’t make sense to hold cash. As with so much investment advice, there is a certain amount of “truthiness” to the statement, but it also doesn’t tell the whole truth.

In regard to market timing, yes, it is virtually impossible to do. In “normal” conditions when risk assets are comfortably within reasonable norms of valuation, it really does not make sense to try to time the market by shifting in and out of stocks and bonds in an attempt to gain a couple of percentage points of performance.

However, and this is another big “however”, stocks are currently near all-time record highs on valuation. Indeed, historically reliable valuation metrics point to negative returns to stocks over the next twelve years.

So, my response is, “Who in their right mind wants to expose themselves to that kind of risk? Sometimes, stocks are just incredibly unattractive, and this is one of those times. Avoiding them at such times isn’t “market timing” so much as reasonably calibrating exposure to opportunity. You don’t go on a picnic in middle of a hurricane either.

There are a few reasons why “market timing” is used to disparage high cash positions. One is simply greed. A large proportion of finance people make money from selling investment products or trading them. If people sit in cash, they aren’t making money.

Another reason is stocks do tend to go up over time, so there is risk involved in betting against that, even when there are solid reasons for doing so. Relatedly, a lot of advisors would prefer to avoid making a nonconsensus call, even if it is well-justified. They would rather fail conventionally, i.e., suffer losses for their clients when everyone else is suffering losses too, than take the chance of doing worse than everyone else.

Finally, “market timing” is also used as disparagement partly because so many investors have short time horizons. Ironically, because it is so hard to determine market direction over such short horizons, there isn’t much of an option to be out of the market if you are evaluated on monthly or quarterly results. By virtue of operating on a short-term basis, it is virtually impossible for many traders to incorporate longer-term risks.

Fortunately, long-term investors don’t need to worry about any of this nonsense. They can let time work for them rather than against them.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.